Who needs privacy? Exploring the relations between need for privacy and personality

Tobias Dienlin

1tobias.dienlin@univie.ac.at

Miriam Metzger

2metzger@ucsb.edu

Abstract

Privacy is defined as a voluntary withdrawal from society. While everyone needs some degree of privacy, we currently know little about who needs how much. In this study, we explored the relations between the need for privacy and personality. Personality was operationalized using the HEXACO personality inventory. Need for privacy was measured in relation to social, psychological, and physical privacy from other individuals (horizontal privacy); need for privacy from government agencies and companies (vertical privacy); as well as need for informational privacy, anonymity, and general privacy (both horizontal and vertical privacy). A sample of 1,550 respondents representative of the U.S. in terms of age, gender, and ethnicity was collected. The results showed several substantial relationships: More extraverted and more agreeable people needed substantially less privacy. People less fair and less altruistic needed more psychological privacy, social privacy, and anonymity, lending some support to the ‘nothing to hide-argument’. Emotionality and conscientiousness showed varied relations with need for privacy. More conservative respondents needed more privacy from the government.Privacy is a major topic of public discourse and academic interest (Dienlin and Breuer 2023). Yet despite its importance, to date we still know surprisingly little about the relation between privacy and personality (Masur 2018, 155). What can we infer about a person if they desire more privacy? Are they more introverted, more risk-averse, or more traditional? Asking these questions seems relevant, not least because people who desire more privacy are often regarded with suspicion, having to justify why they want to be left alone. Consider the “nothing-to-hide” argument (Solove 2007), which is that people who oppose state surveillance only do so because they have something to hide—because if you have nothing to hide, you would have nothing to fear. Is it true that people who desire more privacy are also more dishonest, greedy, or unfair? Or are people simply less extraverted, more diligent, or more prudent? With this paper, we seek to answer the following question: What can we learn about a person’s personality if they say they desire more privacy?

Privacy and Personality

Privacy captures a withdrawal from others or from society in general (Westin 1967). This withdrawal happens voluntarily, and it is under a person’s control (Westin 1967). Privacy is also multi-dimensional. On the broadest level, we can differentiate the two dimensions of horizontal and vertical privacy (Schwartz 1968; Masur, Teutsch, and Dienlin 2018). Whereas horizontal privacy captures withdrawal from other people or peers, vertical privacy addresses withdrawal from superiors or institutions (e.g., government agencies or businesses). In her theoretical analysis, Burgoon (1982) argued that privacy has four more specific dimensions: informational, social, psychological, and physical privacy. Pedersen (1979) conducted an empirical factor analysis of 94 privacy-related items, finding six dimensions of privacy: reserve (“unwillingness to be with and talk with others, especially strangers,” p. 1293); isolation (“desire to be alone and away from others,” p. 1293), solitude (“being alone by oneself and free from observation by others,” p. 1293), intimacy with friends (“being alone with friends,” p. 1293), intimacy with family (“being alone with members of one’s own family,” p. 1293), and anonymity (“wanting to go unnoticed in a crowd and not wishing to be the center of group attention,” p. 1293). Building on these understandings of privacy, in this study we employ a multifaceted model of need for privacy. We focus on vertical privacy with regard to people’s felt need for withdrawal from surveillance by a) the government and b) private companies; horizontal privacy in terms of the perceived need for (c) psychological, (d) social and/or (e) physical withdrawal from other people; and general privacy as captured by people’s felt need for (f) informational privacy, (g) anonymity, and (h) privacy in general. Although all of these dimensions were defined and established in prior research, combining these dimensions into one single comprehensive measure of privacy represents a novel approach.

Acknowledging that various understandings of personality exist, we operationalize personality using the factors and facets of the HEXACO inventory of personality (Lee and Ashton 2018). HEXACO is a large and comprehensive operationalization of personality, and thus is less likely to miss potentially relevant aspects than other operationalizations. The HEXACO model stands in the tradition of the Big Five approach (John and Srivastava 1999). It includes six factors (discussed below), which have four specific facets each. In addition, the HEXACO model includes a sixth factor not present in the Big Five labeled honesty-humility, plus a meta-facet called altruism, which seem particularly well-suited to investigate the nothing-to-hide-argument.

In predicting the need for privacy, we will primarily focus on the facets, because it is unlikely that the very specific need for privacy dimensions will relate closely to more general personality factors (Bansal, Zahedi, and Gefen 2010; Junglas, Johnson, and Spitzmüller 2008). And for reasons of scope, below we cannot discuss all four facets for all six factors. Instead, we focus on those we consider most relevant. However, all will be analyzed empirically.

Predicting the Need for Privacy

So far, only a few studies have analyzed the relation between personality and need for privacy empirically (Hosman 1991; Pedersen 1982, see below). Moreover, we are not aware of a viable theory specifically connecting privacy and personality. Due to the dearth of empirical studies and the lack of theory, in this study we hence adopt an exploratory perspective.

In order to understand how personality might relate to privacy, we can ask the following question: Why do people desire privacy? Privacy is important. But according to Trepte and Masur (2017), the need for privacy is only a secondary need—not an end in itself. Accordingly, privacy satisfies other more fundamental needs such as safety, sexuality, recovery, or contemplation. Westin (1967) similarly defined four ultimate purposes of privacy: (1) self-development (the integration of experiences into meaningful patterns), (2) autonomy (the desire to avoid being manipulated and dominated), (3) emotional release (the release of tension from social role demands), and (4) protected communication (the ability to foster intimate relationships). Privacy facilitates self-disclosure (Dienlin 2014), and thereby social support, relationships, and intimacy (Omarzu 2000). But privacy can also have negative aspects. It is possible to have too much privacy. Being cut-off from others can diminish flourishing, nurture deviant behavior, or introduce power asymmetries (Altman 1975). And privacy can also help conceal wrongdoing or crime.

Privacy has strong evolutionary roots (Acquisti, Brandimarte, and Hancock 2022). Confronted with a threat—for example, the prototypical tiger—people are inclined to withdraw. In the presences of opportunities—for example, the unexpected sharing of resources—people open up and approach one another. Transferred to privacy, we could imagine that if other people, the government, or companies are considered a threat, people are more likely to withdraw and to desire more privacy. Conversely, if something is considered a resource, people might open up, approach others, and desire less privacy (Altman 1976). Privacy also affords the opportunity to hide less socially desirable aspects of the self from others, which may bestow evolutionary advantages in terms of sexual selection or other social benefits and opportunities. Indeed, the need for privacy may have evolved precisely because it offers such advantages.

In what follows, we briefly present each HEXACO factor and how it might relate to need for privacy.

Honesty-Humility & Altriusm

Honesty-humility consists of the facets sincerity, fairness, greed

avoidance, and modesty. The meta-facet altruism measures benevolence

toward others and consists of items such as “It wouldn’t bother me to

harm someone I didn’t like” (reversed).

According to the nothing-to-hide argument, a person desiring more

privacy might be less honest, sincere, fair, or benevolent. People who

commit crimes likely face greater risk from some types of

self-disclosure because government agencies and people would enforce

sanctions if their activities were revealed (Petronio 2010). In those cases, the government

and other people may be perceived as a threat. As a consequence, people

with lower honesty and sincerity might desire more privacy as a means to

mitigate their felt risk (Altman

1976).

Empirical studies have linked privacy to increased cheating behaviors (Corcoran and Rotter 1987; Covey, Saladin, and Killen 1989). Covey, Saladin, and Killen (1989) asked students to solve an impossible maze. In the surveillance condition, the experimenter stood in front of the students and closely monitored their behavior. In the privacy condition, the experimenter could not see the students. Results showed greater cheating among students in the privacy condition, suggesting that in situations with more privacy people are less honest. In a longitudinal sample with 457 respondents in Germany (Trepte, Dienlin, and Reinecke 2013), people who felt they needed more privacy were also less authentic (and therefore, arguably, also less honest and sincere) on their online social network profiles (r = -.48). People who needed more privacy were also less authentic in their personal relationships (r = -.28).

We do not mean to suggest that it is only dishonest people who feel a need for privacy. Everyone, including law-abiding citizens, have legitimate reasons to hide specific aspects of their lives (Solove 2007). A recent study confirmed this notion, finding that people who explicitly endorsed the statement that they would have nothing to hide still engaged in several privacy protective behaviors (Colnago, Cranor, and Acquisti 2023). Our argument is rather that people lower on the honesty HEXACO factor may feel a greater need for privacy. Considering all the evidence, it seems more plausible to us that lack of honesty may indeed relate to an increased need for privacy, and perhaps especially when it comes to privacy from authorities such as government agencies.

Emotionality

Emotionality is captured by the facets of fearfulness, anxiety, dependence, and sentimentality. People who are anxious may be more likely to view social interactions as risky or threatening (especially with strangers or weak ties, Granovetter 1973). Anxious people might hence desire more privacy. People who are more concerned about their privacy (in other words, more anxious about privacy) are more likely to self-withdraw online, for example by deleting posts or untagging themselves from linked content to minimize risk (Dienlin and Metzger 2016). On the other hand, the opposite may also be true: People who are more anxious in general may desire less privacy from others (especially their strong ties), as a means to cope better with their daily challenges or to seek social approval to either verify or dispel their social anxiety.

People who are more anxious might also desire less privacy from government surveillance. Despite the fact that only 18% of all Americans trust their government “to do what is right,” almost everyone agrees that “it’s the government’s job to keep the country safe” (Pew Research Center 2017, 2015). More anxious people might hence consider the government a resource rather than a threat. They might more likely consent to government surveillance, given that such surveillance could prevent crime or terrorism. On the other hand, it could also be that more anxious people desire more privacy from government agencies, at least on a personal level. For example, while they might favor government surveillance of others, this does not necessarily include themselves. Especially if the government is perceived as a threat, as often expressed by members of minority groups, then anxiety might lead one to actually desire more personal privacy.

Extraversion

Comprising the facets social self-esteem, social boldness, sociability, and liveliness, extraversion is arguably the factor that should correspond most closely to need for privacy. Conceptually, social privacy and sociability are closely related. More sociable people are likely more inclined to think of other people as a resource, and thus they should desire less horizontal privacy and less anonymity (e.g., Buss 2001). Given that privacy is a voluntary withdrawal from society (Westin 1967), people who are less sociable, more reserved, or more shy should have a greater need for privacy from others.

This assumption is supported by several empirical studies. People who scored higher on the personality meta-factor plasticity, which is a composite of the two personality factors extraversion and openness, were found to desire less privacy (Morton 2013). People who described themselves as introverted thinkers were more likely to prefer social isolation (Pedersen 1982). Introverted people were more likely to feel their privacy was invaded when they were asked to answer very personal questions (Stone 1986). Pedersen (1982) reported that the need for privacy related to general self-esteem (but not social self-esteem), which in turn is a defining part of extraversion (Lee and Ashton 2018). Specifically, he found respondents who held a lower general self-esteem were more reserved (r = .29), and needed more anonymity (r = .21) and solitude (r = .24). Finally, Larson and Bell (1988) and Hosman (1991) suggested that people who are more shy also need more privacy.

As a result, we expect that people who are more extraverted also need less social privacy and less privacy in general. Regarding the other dimensions of privacy, such as privacy from governments or from companies, we do not expect specific effects.

Agreeableness

Agreeableness has the four facets of forgiveness, gentleness, flexibility, and patience. It is not entirely clear whether or how agreeableness might relate to the need for privacy, although people who are more agreeable are also moderately less concerned about their privacy (Junglas, Johnson, and Spitzmüller 2008). Thus, because need for privacy and privacy concern are closely related, more agreeable people might desire less privacy. To explain, more agreeable people might hold more generous attitudes toward others and are less suspicious that others have malicious motives, and consequently perceive less risk from interacting with others.

Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness consists of the facets organization, diligence, perfectionism, and prudence. Arguably, all facets are about being in control, about reducing relevant risks and future costs. Because control is a central part of privacy (Westin 1967), people who avoid risks, who deliberate, and who plan ahead carefully might prefer to have more privacy because it affords them greater control. Especially if others are considered a threat, being risk averse might increase the desire for more horizontal privacy. Similarly, if government agencies or private companies are considered a threat, risk averse people might have a stronger desire for vertical privacy. In either case, the most cautious strategy to minimize risks of information disclosure would be to keep as much information as possible private. Empirical studies have found that people with a stronger control motive require slightly more seclusion (r = .12) and anonymity (r = .15) (Hosman 1991). People who considered their privacy at risk are less likely to disclose information online (e.g., Bol et al. 2018). Moreover, conscientious people are more concerned about their privacy (Junglas, Johnson, and Spitzmüller 2008).

Openness to experience

Openness to experiences comprises the facets aesthetic appreciation, inquisitiveness, creativeness, and unconventionality. Openness to experience is also considered a measure of intellect and education. In one study it was found that more educated people have more knowledge about how to protect their privacy (Park 2013), which could be the result of an increased need for privacy. Similarly, openness to experience is positively related to privacy concern (Junglas, Johnson, and Spitzmüller 2008).

On the other hand, openness is conceptually the opposite of privacy. People more open to new experiences might not prioritize privacy. Many digital practices such as social media, online shopping, or online dating offer exciting benefits and new experiences, but pose a risk to privacy. People who are more open to new experiences might focus on the benefits rather than the potential risks. Hence, either a positive or negative relationship between need for privacy and openness is possible.

Sociodemographic variables

The need for privacy should also be related to sociodemographic aspects, such as sex, age, education, and income. For example, a study of 3,072 people from Germany found that women desired more informational and physical privacy than men, whereas men desired more psychological privacy (Frener, Dombrowski, and Trepte 2023). In a nationally representative study of the U.S. and Japan, people who were older and who had higher income reported more privacy concern. More educated people possess more privacy knowledge (Park 2013), and as a consequence they might desire more privacy. Ethnicity might also correspond to the need for privacy, perhaps because members of minority groups desire more privacy from the government, although not necessarily from other people. Some minority groups (e.g., Black or Native Americans) often report lower levels of trust in white government representatives (Koch 2019), which might increase the desire of privacy from government agencies. Last, we will examine whether one’s political position is related to the need for privacy. We could imagine that more right-leaning people desire more privacy from the government, but not necessarily from other people. People who are more conservative tend to trust the government slightly less (Cook and Gronke 2005), which might be associated with an increased need for privacy. We will also explore whether a person’s romantic relationship status corresponds to their expressed need for privacy.

Overview of expectations

The arguments discussed above lead to a number of expectations for our data which we delineate below, in order from most to least confidence in terms of identifying significant effects. First, we strongly assume that more extraverted people will desire less privacy, especially less social privacy. We also expect that people who are less honest will express greater need for privacy. We further assume that more conscientious people will desire more privacy and that more agreeable people may desire less privacy. Yet it is largely unclear how privacy needs relate to openness to experience and emotionality. In terms of the sociodemographic variables, we expect females likely need more informational and physical privacy, while males will likely report needing more psychological privacy. Older, more highly educated, and affluent people are also expected to need more privacy, and we anticipate that people who are ethnic minorities or are politically conservative will express greater need for privacy from the government than from other people.

Method

This section describes how we determined the sample size, data exclusions, the analyses, and all measures in the study. The study was conducted as an online questionnaire, programmed with Qualtrics. The survey can be found in the online supplementary material.

Prestudy

This study builds on a prior project in which we analyzed the same research question (Dienlin and Metzger 2019). This study was already submitted to Collabra but rejected. The main reasons were that the sample was too small, that not one coherent personality inventory was used, that most privacy measures were designed ad-hoc, and that the inferences were too ambitious. We hence decided to treat our prior project as a pilot study and to address the criticism by conducting a new study. In this new study, we redeveloped our study design, collected a larger sample, implemented the HEXACO inventory together with established need for privacy measures, and overall adopted a more exploratory perspective. Being our central construct of interest, we also developed a small number of new items to have a more comprehensive measure of need for privacy.

Sample

Participants were collected from the professional online survey panel Prolific. The sample was representative of the US in terms of age, gender, and ethnicity. The study received IRB approval from the University of Vienna (#20210805_067). Participation took on average 16 minutes. We paid participants $2.00 for participation, which equals an hourly wage of $8.00.

To determine sample size, we ran a priori power analyses using the R package simsem (Pornprasertmanit et al. 2021). We based our power analysis on a smallest effect size of interest (SESOI; see below). We only considered effects at least as great as r = .10 as sufficiently relevant to support an effect’s existence (Cohen 1992). To estimate power, we simulated data. We set the correlation between two exemplary latent factors of personality and privacy variable to be \(\Psi\) = .10 (the SESOI). We furthermore set the latent factor loadings to be \(\lambda\) = .85. Adopting an exploratory perspective, and not wanting to miss actually existing effects, we considered both alpha and beta errors to be equally relevant, resulting in balanced/identical alpha and beta errors (Rouder et al. 2016). Because balanced alpha and beta errors of 5% were outside of our budget, we opted for balanced alpha and beta errors of 10%. A power analysis with an alpha and beta error of 10% and an effect size of r = .10 revealed that we required a sample size of N = 1501. To account for potential attrition (see below), we over-sampled by five percent, leading to a planned sample size of N = 1576. In the end, 1569 respondents finished our study, of which we could use 1550, which slightly exceeds our required sample size.

Exclusions and Imputation

We individually checked answers for response patterns such as straight-lining or missing of inverted items. We planned to conservatively remove participants with clear response patterns. Nine participants were excluded because they showed clear patterns, such as straight-lining. We automatically excluded participants who missed the two attention checks we implemented. Overall, 30 participants were filtered out automatically by Prolific, not counting toward our quota. Participants who missed one attention check were checked individually regarding response patterns. No clear patterns emerged. We planned to remove participants below the minimum participation age of 18 years. As no minors took part in our study we did not exclude any participant for this reason. We planned to remove respondents with unrealistically fast responses (three standard deviations below the median response time). The median response time was 14 minutes and the standard deviation 11 minutes. Hence, three SDs below median was -19 minutes, hence not informative. Instead, we decided to remove respondents who took less than five minutes answering the questionnaire, which we considered unreasonably fast. We removed 10 participants for this reason.

We planned to impute missing responses using multiple imputation with predictive mean matching (ten data-sets, five iterations, using variables that correlate at least with r = .10). However, as there were only 27 answers missing in total (0.007 percent), we decided not to impute any data. The final sample size was N = 1550.

Analyses

The factorial validity of the measures and the relations were tested using structural equation modeling. If Mardia’s test showed that the assumption of multivariate normality was violated, we used the more robust Satorra-Bentler scaled and mean-adjusted test statistic (MLM) as estimator (or, in the few cases of missing data MLR plus FIML estimation). We tested each scale in a confirmatory factor analysis. To assess model fit, we used more liberal fit criteria to avoid over-fitting (CFI > .90, TLI > .90, RMSEA < .10, SRMR < .10) (Kline 2016). In cases of misfit, we conservatively altered models using an a priori defined analysis pipeline (see online supplementary material). As a “reality check,” we tested items for potential ceiling and floor effects. If means were below 1.5 or above 6.5, we preregistered to exclude these items. However, as no item was outside these thresholds, no items were excluded.

We wanted to find out who needs privacy, and not so much what causes the need for privacy. Hence, to answer our research question, in a joint model combining all variables (including sociodemographic variables) we analyzed the variables’ bivariate relations. To predict the need for privacy, we first used the six personality factors. Afterward, we predicted privacy using the more specific facets. To get a first idea of the variables’ potential causal relations (Grosz, Rohrer, and Thoemmes 2020), we also planned to run latent structural regression models. However, because model fit was not acceptable, in exploratory analyses we investigated the potential effects in a multiple regression using the mean values of the observed scores.

We used two measures as inference criteria: statistical significance and effect size. Regarding statistical significance, we used an alpha value of 10%. Regarding effect size, we defined a SESOI of r = .10, and thereby a null-region ranging from -.10 to .10. As proposed by Dienes (2014), we considered effects to be meaningful if the confidence interval fell outside of the null region (e.g., .15 to .25 or -.15 to -.25). We considered effects irrelevant if the confidence interval fell completely within the null region (e.g., .02 to .08). And we suspended judgement if the confidence intervals partially included the null region (e.g., .05 to .15).

Fully latent SEMs seldom work instantly, often requiring modifications to achieve satisfactory model fit. Although we explicated our analysis pipeline, there still remained several researcher degrees of freedom. We planned to use fully latent SEM because we consider it superior to regular analyses such as correlation or regression using manifest variables (Kline 2016). However, when all measures were analyzed together in one single SEM model fit was subpar. We hence decided to report the more conservative correlations of average scores. In the online supplementary material, we also share the results of alternative analyses, such as fully latent SEMs.

Measures

All items were answered on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).1 A list of all items that we used are reported in the online supplementary material. The personality and privacy items were presented in random order, and the sociodemographic questions were asked at the end. In the online supplementary material we also report all item statistics and their distribution plots.

Need for privacy

Although there exist several operationalizations of need for privacy (Buss 2001; Pedersen 1979; Frener, Dombrowski, and Trepte 2023; Marshall 1974), we are not aware of one encompassing, comprehensive, and up-to-date scale. Hence, we used both existing scales and self-developed items, some of which were tested in our pilot study. Ad-hoc scales were validated using the following procedure: We (a) collected qualitative feedback from three privacy experts;2 (b) followed the procedure implemented by Patalay, Hayes, and Wolpert (2018) to test (and adapt) the items using four established readability indices (i.e., Flesch–Kincaid reading grade, Gunning Fog Index, Coleman Liau Index, and the Dale–Chall Readability Formula); (c) like Frener, Dombrowski, and Trepte (2023), assessed convergent validity by collecting single-item measures of privacy concern and privacy behavior, for which we expect to find small to moderate correlations; and (d) analyzed all items in confirmatory factor analyses as outlined above.

Overall, we collected 32 items measuring need for privacy, with eight subdimensions that all consisted of four items each. Three subdimensions captured horizontal privacy—namely psychological, social, and physical privacy from other individuals. Psychological and physical privacy were adopted from Frener, Dombrowski, and Trepte (2023). Because Frener, Dombrowski, and Trepte (2023) could not successfully operationalize the dimension of social privacy, building on Burgoon (1982) we self-designed a new social privacy dimension, which in the prestudy showed satisfactory fit. Two subdimensions measured vertical privacy. The first subdimension was government surveillance, which represents the extent to which people want the government to abstain from collecting information about them. The scale was pretested and showed good factorial validity. The second subdimension was need for privacy from companies, which we measured using four new self-designed items. Finally, three subdimensions captured general privacy. The first subdimension was informational privacy, with items adopted from Frener, Dombrowski, and Trepte (2023). The second subdimension was anonymity, which captured the extent to which people feel the need to avoid identification in general. The scale was pretested and showed good factorial validity; one new item was designed for this study. Third, we also collected a new self-developed measure of general need for privacy.

Personality

Personality was measured using the HEXACO personality inventory. The inventory consists of six factors with four facets each, including the additional meta scale of “altruism.”

Results

We first tested the factorial validity of all measures. When analyzed individually, most measures showed satisfactory model fit, not requiring any changes. Some measures showed satisfactory model fit after small adaptions, such as allowing items to covary. In terms of reliability, most measures showed satisfactory results. However, some measures such as altruism, unconventionality, or anonymity showed insufficient reliability. Instead of strongly adapting measures, we decided to maintain the initial factor structure and did not delete any items and we did not introduce substantial changes to the factors. For an overview of all measures, their descriptives and factorial validity, see Table @ref(tab:tab-des). Although individually most of the measures showed good fit, when analyzed together fit decreased substantially, below acceptable levels. As a result, we conservatively decided to analyze our data using the variables’ observed mean scores.

| Variable | M | SD | REL | CFI | TLI | SRMS | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personality | |||||||

| Honesty humility | 4.96 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Sincerity | 4.74 | 1.36 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Fairness | 5.27 | 1.57 | 0.87 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Greed avoidance | 4.36 | 1.42 | 0.74 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Modesty | 5.46 | 1.14 | 0.75 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Altruism | 5.45 | 1.00 | 0.54 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Emotionality | 4.50 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| Fearfulness | 4.61 | 1.24 | 0.70 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Anxiety | 4.78 | 1.37 | 0.80 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| Dependence | 3.84 | 1.19 | 0.80 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Sentimentality | 4.79 | 1.16 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Extraversion | 4.20 | 1.07 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| Social self-esteem | 5.04 | 1.27 | 0.76 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 0.01 | 0.10 |

| Social boldness | 3.58 | 1.34 | 0.72 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Sociability | 3.77 | 1.38 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Liveliness | 4.40 | 1.30 | 0.86 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| Agreeableness | 4.21 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| Forgiveness | 3.39 | 1.26 | 0.84 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Gentleness | 4.61 | 1.13 | 0.74 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Flexibility | 4.26 | 1.10 | 0.65 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Patience | 4.60 | 1.21 | 0.83 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Conscientiousness | 5.15 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Organization | 5.23 | 1.25 | 0.79 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Diligence | 5.17 | 1.13 | 0.70 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Perfectionism | 5.13 | 0.95 | 0.54 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Prudence | 5.07 | 1.07 | 0.73 | 0.97 | 0.91 | 0.04 | 0.10 |

| Openness | 4.79 | 0.97 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Aesth. appreciation | 4.90 | 1.30 | 0.70 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Inquisitiveness | 4.94 | 1.31 | 0.74 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Creativeness | 4.72 | 1.32 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Unconventionality | 4.58 | 1.07 | 0.53 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Need for Privacy | |||||||

| Psychological | 4.29 | 1.16 | 0.73 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Social | 4.31 | 1.29 | 0.73 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Physical | 5.06 | 1.19 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Government | 4.58 | 1.33 | 0.85 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| Companies | 4.49 | 1.09 | 0.72 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Informational | 5.47 | 1.01 | 0.72 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Anonymity | 3.29 | 1.08 | 0.48 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 0.01 | 0.07 |

| General | 5.20 | 1.09 | 0.82 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

Note. REL: Reliability measured via McDonald’s Omega; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index; SRMR = Standardized Root Mean Square Residual; RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

The need for privacy measures showed good convergent validity. If respondents reported higher needs for privacy they were also more concerned about their privacy, with coefficients ranging from r = .21 to r = .73. The only exception was the relation between privacy concerns and the need for social privacy, which was very small (r = .09). If respondents reported higher needs for privacy they also engaged in more privacy behaviors, with coefficients ranging from r = .20 to r = .71 The only exception was the relation between privacy behavior and the need for social privacy, which was virtually nonexistent (r = .01), and the need for physical privacy, which was very small (r = .09). See online supplementary material for all results.

People who reported being less honest and humble needed more anonymity (r = -.17, 90% CI -.21, -.13). Looking at facets, more anonymity was needed by people who reported being less fair (r = -.18, 90% CI -.22, -.14), less modest (r = -.16, 90% CI -.20, -.12), and less altruistic (r = -.25, 90% CI -.29, -.21). People who reported being less fair needed more psychological (r = -.17, 90% CI -.21, -.13), social (r = -.23, 90% CI -.27, -.19), and physical privacy (r = -.17, 90% CI -.22, -.13). Similarly, people who reported being less altruistic also needed substantially more psychological (r = -.28, 90% CI -.32, -.24), social (r = -.28, 90% CI -.32, -.24), and physical privacy (r = -.14, 90% CI -.18, -.10). However, less sincere people needed less privacy from companies (r = .16, 90% CI .12, .20) and less privacy in general (r = .15, 90% CI .11, .19). Effects were small to medium in size.

Several relations between emotionality and need for privacy were found. More emotional people needed less psychological privacy (r = -.20, 90% CI -.24, -.16), less privacy from the government (r = -.14, 90% CI -.18, -.10), less anonymity (r = -.15, 90% CI -.19, -.11)—but also needed more physical privacy (r = .20, 90% CI .16, .24). More anxious respondents needed substantially more social (r = .33, 90% CI .29, .36) and physical privacy (r = .38, 90% CI .34, .41). Similarly, more fearful respondents needed more social (r = .14, 90% CI .10, .18) and physical privacy (r = .27, 90% CI .23, .30). More dependent participants generally needed less privacy, including less psychological (r = -.47, 90% CI -.51, -.44) and social privacy (r = -.29, 90% CI -.32, -.25), less privacy from the government (r = -.15, 90% CI -.19, -.11), and less informational (r = -.18, 90% CI -.22, -.14) and general privacy (r = -.16, 90% CI -.20, -.12). A similar picture for more sentimental participants emerged, who needed less psychological (r = -.27, 90% CI -.31, -.23) and social privacy (r = -.18, 90% CI -.22, -.14) and less anonymity (r = -.18, 90% CI -.22, -.14).

More extraverted people reported they needed a lot less privacy. They wanted less psychological privacy (r = -.46, 90% CI -.49, -.42), social privacy (r = -.77, 90% CI -.78, -.75), and physical privacy (r = -.55, 90% CI -.58, -.53), less informational privacy (r = -.22, 90% CI -.26, -.18) and less anonymity (r = -.19, 90% CI -.23, -.15). Effect sizes were oftentimes large. All facets showed virtually the same relations, with small differences in effect sizes.

More agreeable participants showed a similar pattern. They needed less psychological (r = -.21, 90% CI -.25, -.17), social (r = -.37, 90% CI -.41, -.34), and physical privacy (r = -.38, 90% CI -.41, -.34). The facets showed virtually the same pattern. Effect sizes were substantial, but on the whole smaller than those for extraversion.

Although more conscientious respondents generally needed less privacy, the pattern was varied. More conscientious respondents needed less psychological (r = -.15, 90% CI -.19, -.11) and less social privacy (r = -.24, 90% CI -.28, -.20), as well as less anonymity (r = -.17, 90% CI -.21, -.12). However, when asked about privacy in general more conscientious people responded to need more (r = .17, 90% CI .13, .21). More conscientious people also needed more privacy from companies (r = .14, 90% CI .10, .18). Looking at facets of conscientiousness, more organized people needed less social privacy (r = -.24, 90% CI -.28, -.20) and less anonymity (r = -.14, 90% CI -.18, -.10). More prudent participants needed less anonymity (r = -.17, 90% CI -.21, -.13). More diligent people needed less psychological (r = -.21, 90% CI -.25, -.17), social (r = -.32, 90% CI -.36, -.29), and physical privacy (r = -.18, 90% CI -.22, -.14) as well as less anonymity (r = -.16, 90% CI -.20, -.12)—but also more privacy from companies (r = .14, 90% CI .10, .18) At the same time, more perfectionist respondents reported needing more informational (r = .20, 90% CI .16, .24) privacy, privacy from companies (r = .14, 90% CI .10, .18), and more general privacy (r = .26, 90% CI .22, .30).

Whether or not respondents were open to new experiences was in most cases unrelated to how much privacy they needed. People more open to experiences needed more privacy from companies (r = .15, 90% CI .10, .19) and more privacy in general (r = .15, 90% CI .10, .19). Three facets showed relevant but still small relations. Respondents who reported being more creative needed less psychological (r = -.15, 90% CI -.19, -.11) and less social privacy (r = -.16, 90% CI -.20, -.12). More inquisitive respondents needed less physical privacy (r = -.15, 90% CI -.20, -.11) but more privacy from companies (r = .14, 90% CI .10, .18).

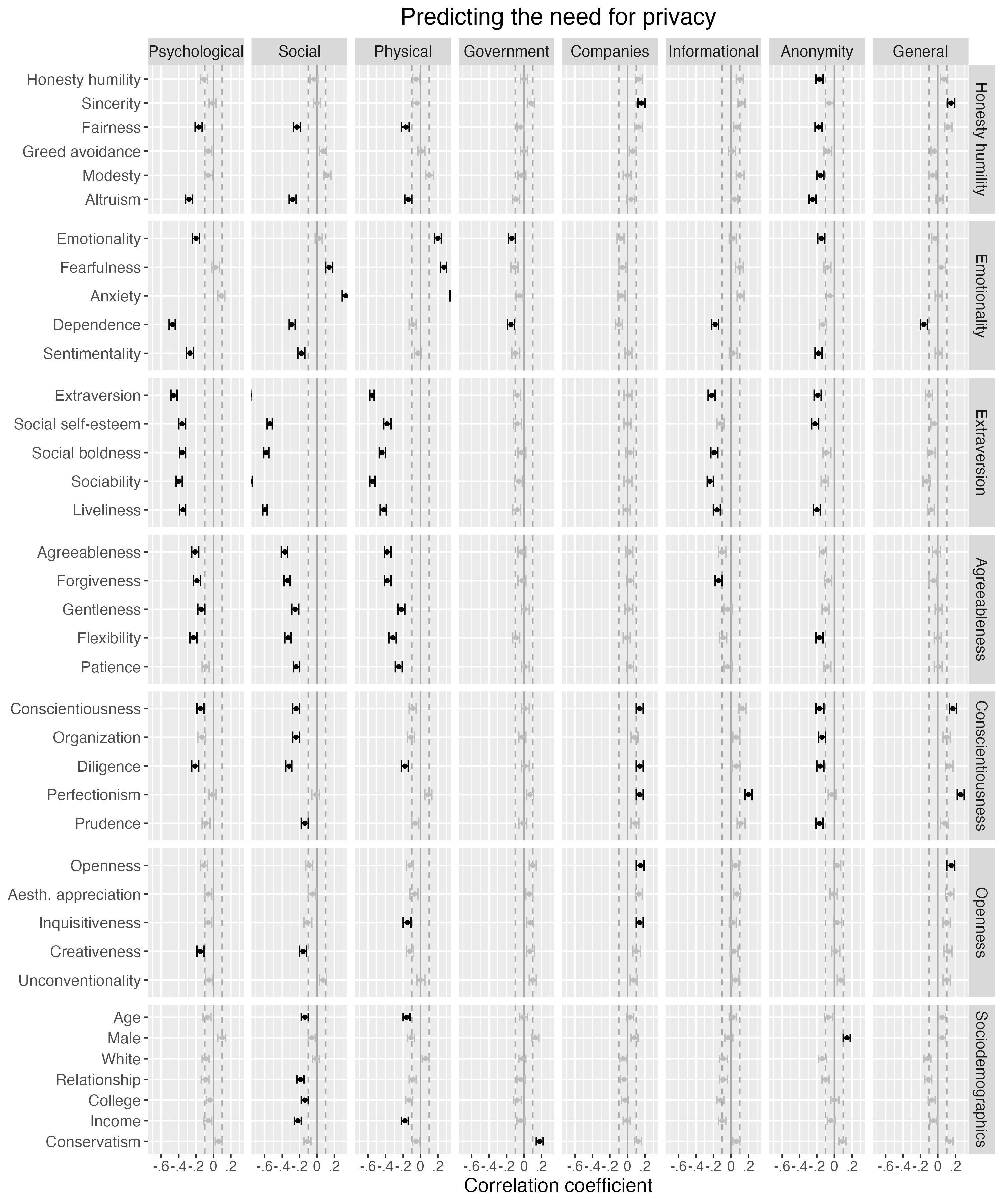

In Table @ref(tab:tab-dim), we report how the personality dimensions predicted need for privacy. In Table @ref(tab:tab-fac), we report how the personality facets predicted need for privacy.

| Personality factors | Psych. | Social | Phys. | Gov. | Comp. | Inform. | Anonym. | General |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Honesty humility | -0.11 | -0.03 | -0.05 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.10 | -0.17 | 0.07 |

| Emotionality | -0.20 | 0.02 | 0.20 | -0.14 | -0.08 | 0.02 | -0.15 | -0.03 |

| Extraversion | -0.46 | -0.77 | -0.55 | -0.08 | 0.01 | -0.22 | -0.19 | -0.10 |

| Agreeableness | -0.21 | -0.37 | -0.38 | -0.03 | 0.02 | -0.10 | -0.13 | -0.01 |

| Conscientiousness | -0.15 | -0.24 | -0.09 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.13 | -0.17 | 0.17 |

| Openness | -0.11 | -0.09 | -0.12 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.15 |

| Personality factors | Psych. | Social | Phys. | Gov. | Comp. | Inform. | Anonym. | General |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Honesty humility | ||||||||

| Sincerity | -0.01 | 0.00 | -0.04 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.12 | -0.06 | 0.15 |

| Fairness | -0.17 | -0.23 | -0.17 | -0.04 | 0.13 | 0.07 | -0.18 | 0.12 |

| Greed avoidance | -0.06 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.01 | -0.07 | -0.04 |

| Modesty | -0.06 | 0.12 | 0.10 | -0.03 | 0.00 | 0.10 | -0.16 | -0.06 |

| Altruism | -0.28 | -0.28 | -0.14 | -0.09 | 0.04 | 0.04 | -0.25 | 0.02 |

| Emotionality | ||||||||

| Fearfulness | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.27 | -0.11 | -0.06 | 0.10 | -0.08 | 0.04 |

| Anxiety | 0.09 | 0.33 | 0.38 | -0.05 | -0.07 | 0.11 | -0.05 | 0.01 |

| Dependence | -0.47 | -0.29 | -0.09 | -0.15 | -0.10 | -0.18 | -0.13 | -0.16 |

| Sentimentality | -0.27 | -0.18 | -0.03 | -0.10 | 0.01 | 0.02 | -0.18 | 0.01 |

| Extraversion | ||||||||

| Social self-esteem | -0.36 | -0.54 | -0.38 | -0.08 | 0.00 | -0.12 | -0.22 | -0.04 |

| Social boldness | -0.36 | -0.58 | -0.44 | -0.03 | 0.03 | -0.19 | -0.09 | -0.08 |

| Sociability | -0.40 | -0.76 | -0.55 | -0.06 | 0.01 | -0.24 | -0.11 | -0.13 |

| Liveliness | -0.35 | -0.59 | -0.42 | -0.08 | -0.01 | -0.16 | -0.20 | -0.08 |

| Agreeableness | ||||||||

| Forgiveness | -0.19 | -0.34 | -0.38 | -0.02 | 0.03 | -0.14 | -0.07 | -0.05 |

| Gentleness | -0.14 | -0.25 | -0.22 | 0.01 | 0.01 | -0.04 | -0.10 | 0.01 |

| Flexibility | -0.23 | -0.33 | -0.32 | -0.09 | -0.01 | -0.09 | -0.17 | 0.00 |

| Patience | -0.09 | -0.24 | -0.25 | 0.01 | 0.03 | -0.04 | -0.08 | 0.01 |

| Conscientiousness | ||||||||

| Organization | -0.13 | -0.24 | -0.11 | -0.02 | 0.08 | 0.06 | -0.14 | 0.10 |

| Diligence | -0.21 | -0.32 | -0.18 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.06 | -0.16 | 0.13 |

| Perfectionism | -0.01 | -0.01 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.20 | -0.03 | 0.26 |

| Prudence | -0.09 | -0.14 | -0.06 | -0.01 | 0.09 | 0.11 | -0.17 | 0.08 |

| Openness to experiences | ||||||||

| Aesth. appreciation | -0.06 | -0.05 | -0.07 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.07 | -0.01 | 0.14 |

| Inquisitiveness | -0.06 | -0.11 | -0.15 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.10 |

| Creativeness | -0.15 | -0.16 | -0.12 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.12 |

| Unconventionality | -0.05 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.10 |

Not many meaningful relations between sociodemographic variables and need for privacy were found. Older participants needed less social (r = -.14, 90% CI -.18, -.10) and less physical privacy (r = -.16, 90% CI -.20, -.12). Male participants needed more anonymity (r = .14, 90% CI .10, .18). Less social privacy was needed by people in a relationship (r = -.19, 90% CI -.23, -.15), with a college degree (r = -.14, 90% CI -.18, -.10), and with higher income (r = -.22, 90% CI -.26, -.18). People with higher income also reported needing less physical privacy (r = -.18, 90% CI -.22, -.14). More politically conservative respondents reported needing more privacy from the government (r = .18, 90% CI .14, .22).

In Table @ref(tab:tab-ses), we report how sociodemographics predicted need for privacy. Figure @ref(fig:fig-cor) summarizes how all of the variables—dimensions, facets, and sociodemographics—predicted the need for privacy.

| Sociodemographics | Psych. | Social | Phys. | Gov. | Comp. | Inform. | Anonym. | General |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | -0.07 | -0.14 | -0.16 | -0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | -0.07 | 0.05 |

| Male | 0.10 | -0.06 | -0.11 | 0.13 | 0.08 | -0.03 | 0.14 | 0.05 |

| White | -0.09 | -0.01 | 0.06 | -0.02 | -0.05 | -0.09 | -0.14 | -0.12 |

| Relationship | -0.09 | -0.19 | -0.09 | -0.04 | -0.04 | -0.09 | -0.10 | -0.11 |

| College | -0.04 | -0.14 | -0.13 | -0.08 | -0.03 | -0.12 | 0.00 | -0.07 |

| Income | -0.06 | -0.22 | -0.18 | -0.04 | -0.01 | -0.10 | -0.04 | -0.05 |

| Conservatism | 0.06 | -0.11 | -0.05 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.13 |

Results of bivariate correlations between personality and need for privacy. Bold: Effects that are statistically significant and larger than = .10 / -.10.

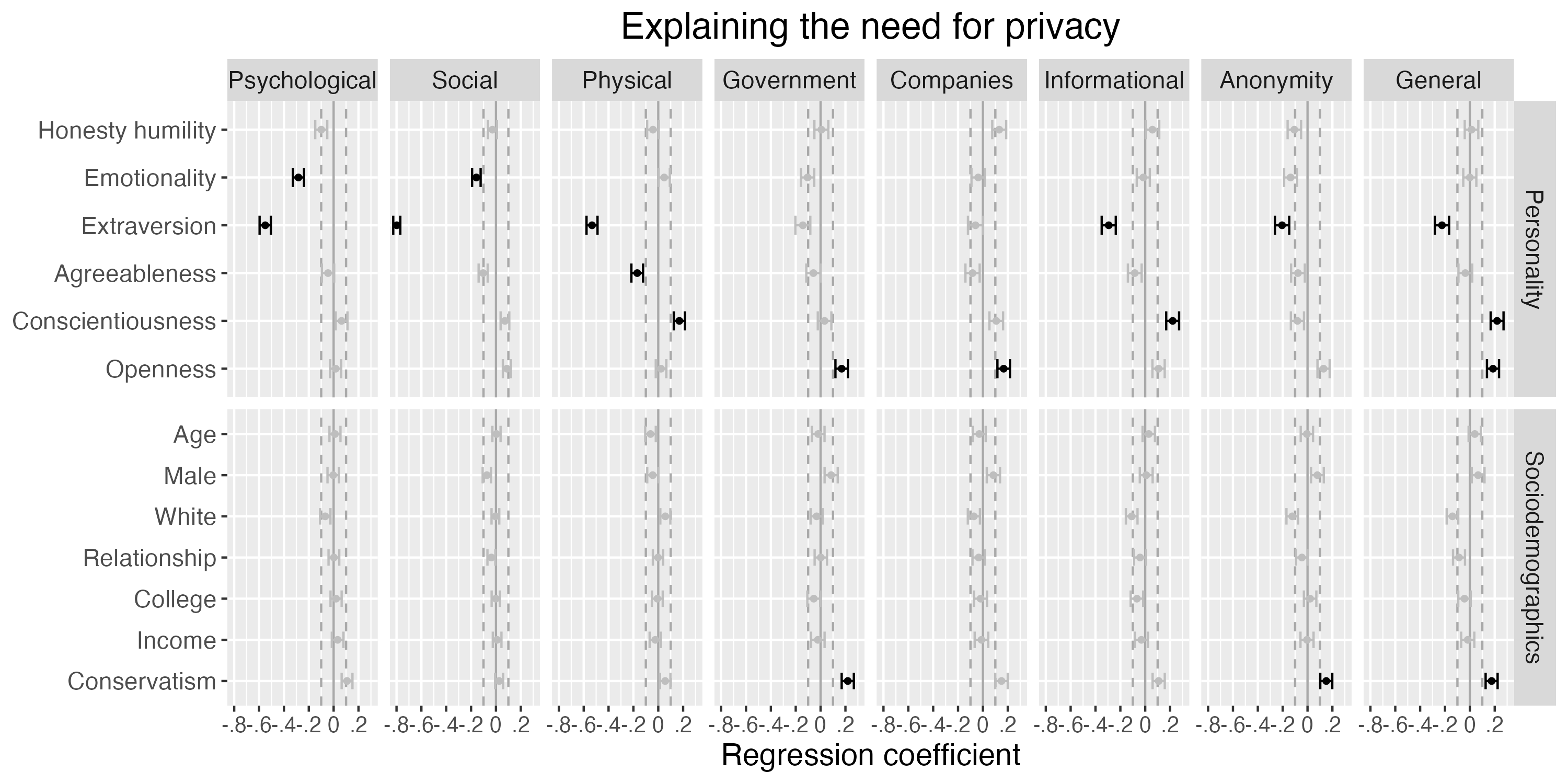

In exploratory analyses we analyzed how personality facets might have potentially caused need for privacy, using multiple regressions in which we controlled for all personality dimensions and sociodemographic variables. We found that the need for psychological privacy was explained by two variables: extraversion (\(\beta\) = -.55, 90% CI -.60, -.50) and emotionality (\(\beta\) = -.28, 90% CI -.33, -.24). The need for social privacy was also potentially affected by extraversion and emotionality. Being more extraverted substantially decreased the need for psychological privacy (\(\beta\) = -.80, 90% CI -.83, -.77), as did being more emotional (\(\beta\) = -.16, 90% CI -.19, -.12). Physical privacy was determined by again extraversion, but also by agreeableness and conscientiousness. Being more extraverted appeared to decrease the need for physical privacy (\(\beta\) = -.53, 90% CI -.58, -.49); being more agreeable likewise decreased the need for physical privacy (\(\beta\) = -.17, 90% CI -.22, -.12); however, being more conscientious increased the need for physical privacy (\(\beta\) = .17, 90% CI .12, .21). The need for privacy from the government was affected by the two factors of openness and conservatism. Being more open to new experiences potentially increased the need for privacy from the government (\(\beta\) = .17, 90% CI .12, .22), as did being more politically conservative (\(\beta\) = .22, 90% CI .17, .27). The need for privacy from companies was affected by the openness to new experiences only. Being more open to new experiences potentially increased the need for privacy from companies (\(\beta\) = .17, 90% CI .12, .22). Being extraverted and conscientious affected the need for informational privacy. Whereas being more extraverted decreased the need for informational privacy (\(\beta\) = -.29, 90% CI -.35, -.24), being more conscientious increased the need for informational privacy (\(\beta\) = .22, 90% CI .17, .27) in our data. The need for anonymity was meaningfully affected only by extraversion. More extraverted people need less anonymity (\(\beta\) = -.20, 90% CI -.26, -.15). Finally, the general need for privacy was affected by four variables. Being extraverted again decreased the general need for privacy (\(\beta\) = -.22, 90% CI -.28, -.17). However, the general need for privacy was increased by being more conscientious (\(\beta\) = .22, 90% CI .17, .27), more conservative (\(\beta\) = .18, 90% CI .13, .22), and more open to experiences (\(\beta\) = .19, 90% CI .14, .23).

Figure @ref(fig:fig-reg) shows how privacy dimensions and sociodemographics potentially affected the need for privacy.

Results of multiple regression. Bold: Effects that are statistically significant and larger than = .10 / -.10.

Discussion

In this study we analyzed the relation between personality and need for privacy. The data came from N = 1550 respondents from the US, representative in terms of age, gender, and ethnicity. The results showed several meaningful relations between personality and need for privacy that were statistically significant and not trivial in size (i.e., 90% CI r \(\geq\) .10).

As expected, the need for privacy was most closely related to extraversion. Participants who were more extraverted generally needed substantially less privacy. The relation between extraversion and social privacy was particularly large, suggesting that social privacy and extraversion overlap conceptually. In addition, almost all subscales of extraversion showed similar patterns: People with greater social boldness, self-esteem, or liveliness all needed substantially less privacy from other people and less physical, psychological, and informational privacy. Extraverted people reach out to others, share their inner lives, are confident around others—which reflects in a reduced need for privacy.

The personality factor next closely related to need for privacy was agreeableness. More agreeable respondents needed less privacy in general. In particular, more agreeable respondents needed substantially less psychological, social, and physical privacy. Although this finding aligned with our prior expectation, we were surprised by the strength of the relations. Because more agreeable people have fewer conflicts with others and are more easy to get along with, they likely see others less as a threat, and hence have a reduced need for privacy. Like as was found for extraversion, no relevant relations with need for privacy from government and companies exist, suggesting that agreeableness and extraversion—personality traits mostly relevant in interpersonal contexts—might not extend to the need for privacy in these public domains.

In analyzing how the honesty humility factor relates to need for privacy, we investigated the nothing-to-hide argument. As expected, our results provided support for the nothing-to-hide argument, especially with regard to the need for anonymity. Respondents who needed more anonymity were less honest, less fair, less modest, and less altruistic. Respondents who were less fair and less altruistic also needed more psychological, social, and physical privacy. Less honest participants desired more anonymity and privacy from other people, be it psychologically, socially, or physically. These findings align with a recent study indicating that individuals with lower levels of honesty are more inclined to seek anonymity online, for example to engage in toxic communication (Nitschinsk et al. 2023). However, honesty was unrelated to the need for privacy from government and companies or informational and general privacy. If anything, people who were more sincere actually desired more privacy from companies and more privacy in general. So although less honest people needed more privacy in several dimensions, this pattern is not uni-dimensional but somewhat varied and nuanced.

Emotionality showed mixed relations with need for privacy, which confirmed our ambivalent a priori expectations. More emotional people desired less psychological privacy, less privacy from the government, and less anonymity. At the same time, they needed more physical privacy. Whereas they may want tighter relational bonds to people close to them, they appear to be warier of strangers entering their personal physical spaces. Fearful and anxious people wanted more social and more physical privacy, while dependent and sensitive people wanted less. It seems that more emotional people have a subtle and varied approach to privacy depending on the nature of their emotionality. This is consistent with research on discrete emotions which finds that certain negative emotions—fear and anxiety in particular—evoke the aversive motivational system that facilitates avoidance behaviors, whereas other emotions, possibly including dependence and social sensitivity, activate an appetitive motivational system that facilitates approach behaviors (Phaf et al. 2014).

Contrary to our expectations, conscientiousness showed varied relations with need for privacy. More conscientious people needed less psychological and social privacy and less anonymity. Asked about privacy from companies and privacy in general, however, they answered they needed more. More perfectionist people preferred both more informational privacy, privacy from companies, and more privacy in general—perhaps to have more options and leeway to adapt plans or hide imperfections. More diligent people needed less privacy from other people, less psychological privacy, and less physical privacy. Speculating about a potential explanation, we could imagine that similar to the nothing-to-hide argument more diligent people might have less to be afraid of and so are more open to public scrutiny.

Although openness might be the opposite of privacy semantically, empirically only a handful of meaningful relations with need for privacy were found. And interestingly, the main dimension showed that more open people actually wanted more privacy from companies and more privacy in general. The facet creativity was meaningfully related to psychological and social privacy, such that more creative people needed less psychological and social privacy. It might be that more creative people generally think of others as resources, thriving from their inputs and exchanges. More inquisitive people needed less physical privacy from others. They, too, might see others as a resource, valuing closer exchanges with people unknown to them.

In addition, we looked at relations between need for privacy and various sociodemographic variables. Contrary to our expectations, older participants desired less privacy from others, both socially and physically. This was surprising, for example given that older people report increased online privacy concern (Kezer et al. 2016). It is an open question as to whether this relation represents a developmental mechanism or a difference between cohorts. Research suggests that older people have fewer social interactions than younger people (Ortiz-Ospina, Giattino, and Roser 2024), which could result in a lower need for social and physical privacy. But it could also be a difference between cohorts. Younger people nowadays have fewer in-person social contacts than before, often attributed to increases in time spent online (Twenge, Spitzberg, and Campbell 2019). Hence, it could also be that younger generations prefer more solitude than the generations beforehand.

We expected that males would desire more psychological privacy but less social and physical privacy than females. Although in our data these relations were statistically significant, the effects sizes were too small to be considered meaningful. The only meaningful gender effect we found was with regard to anonymity. Males needed more anonymity than females. This finding is in line with the fact that women more readily view themselves as vulnerable and targets for victimization than do men (Lewyn 1993).

People in relationships needed less social privacy. This makes sense as being in a relationship implies a minimum commitment of openness to others. Contrary to our expectations, respondents with a college degree and with greater income all reported lower levels of need for social privacy. Having fewer educational and financial resources might result in greater social stigma, leading to an increased need for social privacy. More politically conservative respondents needed more privacy from the government—which we expected given the general political tendencies of conservatives to prefer fewer state regulations and interferences. Finally, no meaningful relations with ethnicity were found. For example, contrary to what we expected we did not find that minority groups desired more privacy from the government in our data.

The results above are based on correlations and analyzed the variables’ relationships. To analyze the potential impact of personality on need for privacy, in exploratory analyses we also ran several multiple regression analyses. Here, we estimated the relations between each personality and need for privacy dimension while controlling for all other personality dimensions and sociodemographics. Results were comparable, in that extraversion turned out to be the major potential cause of need for privacy. However, there were also some differences. Most notably, results implied that being more conscientious increases the need for physical, informational, and general privacy. Similarly, being more open to new experiences might increase the need for privacy from the government, from companies, and for privacy in general. Finally, multiple regression results suggested that being conservative does not only increase the need for privacy from the government but also for privacy in general. All other sociodemographic variables ceased to be significant.

Looking at the results more broadly, we make five general observations. First, it makes sense to differentiate different levels of need for privacy. Many personality traits showed meaningful relations with some dimension, yet no or even opposite relations with others. To illustrate, whereas more conscientious people desired less psychological privacy and less privacy from other, when asked about privacy in general and privacy from companies they needed more. General need for privacy may rather represent a cognitive appraisal, whereas social or psychological privacy might be more experienced-based and psychological. In any case, our results argue for a more rather than less nuanced strategy for measuring privacy attitudes.y

Second, the need for privacy from companies and the government, both vertical forms of privacy, showed only a couple of meaningful relations with personality. The most notable relation was that conservative people needed substantially more privacy from the government. Most relations between privacy needs and personality were found for forms of horizontal privacy, suggesting that personality has more influence on the more social and interpersonal aspects of privacy. So while the demographic variable of political ideology more strongly affected vertical privacy needs, personality aspects appear to better explain horizontal privacy needs.

Third, although we found support for the nothing-to-hide-argument, our results also support the reasoning of the argument’s critics. Although desiring more anonymity was related to less honesty, fairness, and altruism, these relations were not particularly large. Next, it is insufficient to assume that anonymity is needed only by people with reduced honesty. Less emotional, less extraverted, and more conscientious people also needed more anonymity. Finally, when analyzed together with the other predictors, honesty and humility ceased to be a relevant predictor.

This leads to our fourth general observation. Our main interest was to determine the personality factors predicting the need for privacy. What can we learn about a person given their need for privacy? We first analyzed this question in correlation analyses. However, when we further explored potential causal effects using multiple regression analysis (Grosz, Rohrer, and Thoemmes 2020), a somewhat different picture emerged. Several of the bivariate relationships we initially observed disappeared. These results suggest that some of the correlations we found might not be due to a direct causal process but could instead be explained by shared variance with a third confounding factor. Additionally, some causal effects that were not apparent in the correlation analyses became significant in the multiple regressions. Specifically, conservatism became more relevant when we included additional control variables, suggesting that an increase in conservatism leads to a greater desire for anonymity and privacy in general.

Finally, our results have significant implications for privacy theory, suggesting new avenues for further research. Given the close relationship between personality and privacy, it is worthwhile to examine how personality traits interact with specific privacy models and theories. For instance, personality could influence the privacy calculus model (Kezer, Dienlin, and Baruh 2022). Extraverted individuals, who tend to view others as resources, might perceive greater benefits in sharing information online and therefore be more open in their sharing behaviors. Conversely, anxious individuals, who are more likely to see others as threats, might have heightened concerns about privacy, leading to a reduced willingness to share information online.

Limitations

Not all personality and privacy measures showed good fit. Especially when analyzed together, fit was not satisfactory. Likewise, some measures such as altruism, unconventionality, or anonymity showed low reliability. The results of these variables thus need to be interpreted more cautiously.

Instead of deleting items or changing the factor structure, to avoid over-fitting we decided to maintain the measures’ original factor structure. For this reason, instead of reporting the results from latent structural equation modelling, we reported the results of the correlations of the observed variables’ means. Interested readers can find the results of the latent analyses in our online supplementary material. The results are highly comparable, with the major difference that effect sizes in the latent models tended to be larger. The results reported here are hence more conservative and likely underestimate the true effect sizes. This underscores the need for further optimizing measures of personality and privacy.

In our exploratory analyses, we aimed to investigate the potential causal effects of personality on the need for privacy by controlling for potential confounders, including other personality dimensions and sociodemographic variables. However, it is important to note that this is only a preliminary approach, as there are likely additional variables that could further explain the relationships. Future research should explore the potential causal relationships in a more systematic and comprehensive manner.

Our findings are specific to the U.S. context. Previous research indicates that although privacy is a universal concept, attitudes and practices vary significantly across different cultures and countries (Altman 1977). It is possible that the relationship between personality and the need for privacy manifests differently in various settings. We hope this study will serve as a catalyst for future research in this area.

References

Contributions

Conception and design: TD, MM. Data acquisition: TD. Code: TD. Analysis and interpretation of data: TD, MM; First draft: TD; Revisions & Comments: TD & MM.

Funding Information

During the conception and data collection of the prestudy, TD was funded by The German Academic Scholarship Foundation (German: Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes), which financially supported a research stay at UCSB. During some time working on the article and while at University of Hohenheim, TD was funded by the Volkswagen Foundation (German: Volkswagenstiftung), grant “Transformations of Privacy”. TD is now funded by a regular and not-tenured assistant professorship at University of Vienna. MM is funded by a regular and tenured full professorship at UCSB.

Conflict of Interests

Both authors declare no conflict of interests.

Supplementary Material

All the stimuli, presentation materials, analysis scripts, and a reproducible version of the manuscript can be found on the open science framework (https://osf.io/e47yw/). The paper also has a companion website where all materials can be accessed (https://tdienlin.github.io/Who_Needs_Privacy_RR).

Data Accessibility Statement

The data are shared as a scientific use file on AUSSDA at https://doi.org/10.11587/IC66GC (Dienlin and Metzger 2024).

Note that the HEXACO inventory normally uses 5-point scales. Because we were not interested in comparing absolute values across studies, we used 7-point scales to have a uniform answer format.↩︎

The three experts who provided feedback were Moritz Büchi (University of Zurich), Regine Frener (University of Hohenheim), and Philipp Masur (VU Amsterdam).↩︎